Search This Blog

For those nocturnal animals out there, who are comfortable in the darkness of the theatre. If you share the same love for cinema, this blog is the place for you. You can find reviews, personalised animated gifs, lists of unusual films and more.

Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

You Were Never Really Here Review/List of 10 films exploring masculinity directed by women.

Lynne Ramsay

Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Alessandro Nivola, Ekaterina Samsonov, Judith Anna Roberts

Country: United Kingdom, France, United States

Probably not too many people are familiar with Scottish director Lynne Ramsay, one of the most outstanding female directors working today. In 18 years she made four fantastic films, starting from her powerful and compelling debut the Ratcatcher (1999) followed by her poetic Morvern Callar (2002). Her films share the same unnerving darkness, the same abstract approach to the character's psyche and the same visceral brutality. Her previous masterwork was 2011s We need to Talk About Kevin, in which Tilda Swinton likely gave her most complex performance of her eclectic career as she plays a mother torn apart by the inexplicable actions of her sadistic son (Ezra Miller). After almost seven years, You Were Never Really Here (previously called "A Beautiful Day") pays off the long wait, since it's probably among the best films of the year, by some considered the "Taxi Driver of the 21st Century".

The plot goes on the back burner as it is almost superfluous. As in We Need to Talk About Kevin, Ramsay is more interested in exploring the character's subconscious. Instead of following a linear storyline, she follows the chaotic trail of thought of a tortured mind. She intends to dive under the unpenetrable skin of her anti-hero Joe, played by Joaquin Phoenix, an ex-war vet turned into a hitman whose task is to rescue underage girls from a sex trafficking ring and mercilessly kill the perpetrators. The New York Senator offers him a considerable sum of money to save his abducted daughter, Nina. He asks him to be brutal.

Adapted from Jonathan Ames's book, You Were Never Really Here won Best Screenplay at Cannes, which was an interesting choice considering the movie has very scarce dialogue. The Jury also awarded the title of Best Actor to a marvellous Joaquin Phoenix, as he embodies perfectly the haunting darkness of his character.

Joe's soul is a wounded animal, that screams in agony, trapped inside the contorted asymmetrical body of a ruthless hitman armed with a hammer. The scars caused by unimaginable trauma inflicted by his abusive father during his childhood and the horrors he witnessed during the war translate on the outside with real keloid scars and dark bruises over his body.

He seems like he can barely speak. He doesn’t know how to communicate if not through violence since violence it’s the only thing he knows. He is like a silent ghost floating around the streets of a polluted New York leaving no trace (which makes the title particularly accurate). Self-harm seems to be part of his ordinary routine. He wraps a plastic bag around his head, stopping when it’s almost too late, or like the sword of Damocles, he dangles a knife precariously above his eye while he is laying down on the bed. What we know about Joe's past, is only through horrific glimpses inside his head which Ramsay delivers without warning. These unsettling images crawl under the viewer's skin, lingering in the imagination without giving an exact answer.

The masterful soundtrack of Radiohead's Johnny Greenway amplifies this impressionistic imagery. Fresh from producing the mystical, sumptuous and elegant music in Paul Thomas Anderson's Phantom Thread, Greenway seems perfectly comfortable in distorting the violin's sublime sound and creating a dirty, clutching and haunting soundtrack, which acoustically translates the darkest reverberations of the human soul, as only Mica Levi in Under the Skin (2013) ever did before.

As you can imagine, You Were Never Really Here is a punch in the guts. However, Ramsay is not interested in showing gratuitous violence. She focuses more on the aftermath of the fight rather than on the act itself, which we always witness from afar, or on the black and white screen of a CCTV Camera. Among all this blood, Ramsay captures moments of genuine tenderness. After a violent fight with two men who came into his house to kill him, Joe lies on the floor with the dying shooter, holding his hand and they both quietly sing along to Charlene's “I've Never Been to Me” on the radio. A scene that, if not handled well, would have indeed been a parody. Instead, we almost feel honoured to peer a glimpse of innocence in this nihilistic world.

We witness Joe's more delicate side when he spends time with his mother, who seems to be his only human connection. In one scene Psycho(1960) is playing on TV, as if the director jokingly intends that there is an obsessive relationship between them both.

The character of Nina becomes almost a symbol of innocence, Joe's chance to make his horrific life and this corrupted world a better place, at least for someone. A bit like the teenage prostitute "Iris", played incredibly well by a 12 years old Jodie Foster, was for Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) in Taxi Driver (1976).

Ramsay ends with an open (as well as) strangely optimistic scene. We don't know what will happen to our anti-hero, but we leave him in a moment of serenity. In this challenging and hopeless scenario, Ramsay invites us to grasp those rare moments of quiet beauty that we can find in the mundane. Likely horrible things are going to happen to Joe, and this scene is only the calm before the storm, but it remains a beautiful day.

Movies you might like if you like You Were Never Really Here:

Taxi Driver (1976) by Martin Scorsese

Drive (2011) by Nicolas Winding Refn

We Need To Talk About Kevin (2011) by Linney Ramsay

The Master (2012) by Paul Thomas Anderson

We Need To Talk About Kevin (2011) by Linney Ramsay

The Master (2012) by Paul Thomas Anderson

Niche List of the week

10 Film about Men and Masculinity directed by Women

Female filmmakers have always been a rarity. Cinema might be the most predominately male art form, considering that only 4% of Hollywood Studio movies are directed by women. If you ask a random person in the street to name a female director, he/she might struggle to come up with a someone. The history of women behind the camera is maybe short, but not necessarily weak. From Alice Guy Blaché, who was among the pioneer of the silent era and likely the first female director, to Dorothy Arzner, who was the only female filmmaker to survive the unfriendly environment in Hollywood in the 30s.

From Ida Lupino, the first woman to ever direct a film noir, to Lina Wertmuller, the first woman to be ever nominated to the Oscar as Best Director (1975). From avant-garde experimental filmmaker Maya Deren to feminist revolutionary talents like Chantel Akerman and Agnès Varda. From Kathryn Bigelow war and action movies to Patty Jenkins commercial blockbuster Wonder Woman.

The Bechdel Test is a method of evaluation for evaluating the portrayal of women in fiction. How much screen time female characters receive? What does the female character say in the film? Are those two female characters talking about something other than a man? Are these feminist films? Funnily enough, these list of films directed by women probably will fail the rigid criteria of the Bechdel Test.

What many female artists try to do is to change the predominately male gaze in cinema, which often treated women as commodities, relegated to more passive characters than their male co-workers. It's interesting to see how some female directors centre their stories around a male character, and how they explore the theme of masculinity without relying on stereotypes but depicting complex characters who can be both violent and vulnerable. The films in this list deal in different ways and from different points of views with the societal pressures, the camaraderie, the male bonding, the internalised misogyny and the fragility behind machismo.

10 Film about Men and Masculinity directed by Women

Female filmmakers have always been a rarity. Cinema might be the most predominately male art form, considering that only 4% of Hollywood Studio movies are directed by women. If you ask a random person in the street to name a female director, he/she might struggle to come up with a someone. The history of women behind the camera is maybe short, but not necessarily weak. From Alice Guy Blaché, who was among the pioneer of the silent era and likely the first female director, to Dorothy Arzner, who was the only female filmmaker to survive the unfriendly environment in Hollywood in the 30s.

From Ida Lupino, the first woman to ever direct a film noir, to Lina Wertmuller, the first woman to be ever nominated to the Oscar as Best Director (1975). From avant-garde experimental filmmaker Maya Deren to feminist revolutionary talents like Chantel Akerman and Agnès Varda. From Kathryn Bigelow war and action movies to Patty Jenkins commercial blockbuster Wonder Woman.

The Bechdel Test is a method of evaluation for evaluating the portrayal of women in fiction. How much screen time female characters receive? What does the female character say in the film? Are those two female characters talking about something other than a man? Are these feminist films? Funnily enough, these list of films directed by women probably will fail the rigid criteria of the Bechdel Test.

What many female artists try to do is to change the predominately male gaze in cinema, which often treated women as commodities, relegated to more passive characters than their male co-workers. It's interesting to see how some female directors centre their stories around a male character, and how they explore the theme of masculinity without relying on stereotypes but depicting complex characters who can be both violent and vulnerable. The films in this list deal in different ways and from different points of views with the societal pressures, the camaraderie, the male bonding, the internalised misogyny and the fragility behind machismo.

- The Hitch-Hiker (1953) by Ida Lupino

“This is the true story of a man and a gun and a car.” This was the opening logline of Lupino's nation-wide propaganda campaign anti-hitchhiking. Ida Lupino was the only notable female director working in Hollywood at the time. She was also the only woman to ever trespassed a "male" genre like the noir. Hitch-Hiker is an atypical noir where desertic landscapes replace the dark city streets people were so accustomed. It's a gritty, man-centred thriller on the road. It follows two travellers who make the terrible mistake to pick up a psychotic man who will take them hostage, played by a terrific William Talman.

- Le Bonheur (1965) by Agnès Varda

No many filmmakers have such a diverse, radical and prolific filmography as Agnès Varda. How many directors can say to have been pioneers of the French Nouvelle Vague, political activist and experimented with documentaries, social films and art-installations?

Le Bonheur is another example of her mastery, a delicate and intelligent film on the hermetically sealed world of male privilege and gender roles. It opens with the perfect family picture: An idyllic summer, warm pastel colours, picnic blankets listening to Mozart and Pinterest sunflowers. The movie is centred around a young 'happy" couple François and Thérèse (actual husband and wife Jean-Claude and Claire Drouot). François is a symbolic everyman who will start an affair in the pursuit of his happiness. Highlighting the imbalances of the 60's sexual revolution, Varda explores the patriarchal dynamic of this married couple, where her joy is measured accordingly her husband's comfort. Still incredibly modern.

Le Bonheur is another example of her mastery, a delicate and intelligent film on the hermetically sealed world of male privilege and gender roles. It opens with the perfect family picture: An idyllic summer, warm pastel colours, picnic blankets listening to Mozart and Pinterest sunflowers. The movie is centred around a young 'happy" couple François and Thérèse (actual husband and wife Jean-Claude and Claire Drouot). François is a symbolic everyman who will start an affair in the pursuit of his happiness. Highlighting the imbalances of the 60's sexual revolution, Varda explores the patriarchal dynamic of this married couple, where her joy is measured accordingly her husband's comfort. Still incredibly modern.

- The Seduction of Mimi, Mimi Metallurgico Ferito Nell'Onore (1972) by Lina Wertmüller

One of the few people that make me feel proud of being Italian. Lina Wertümuller was the first woman to be nominated to the Academy Awards for Best Director with Seven Beauties (1977). Her work is always crass, politically incorrect, violent and uncomfortably funny, where sex is never sexy, but becomes an allegory of social power, class and gender roles. Pairing her favourite couple again, Giancarlo Giannini and Mariangela Melato, in this hilarious satire on the exploitation of the working class in Italy. It follows "Mimi" a married Sicilian metalworker who escape to the North after he refused to vote for the Mafia and will fall in love with a radical Northerner. Possessive, jealous and morally corrupted, he is the embodiment of fragile machismo. After he cheated on his spouse (He had a baby with Mariangela Melato's character), his "honour" is wounded when he finds out that his abandoned wife cheated on him.

- Point Break (1991) by Kathryn Bigelow

Kathryn Bigelow is the first (and only) woman to win the Oscar for Best Director with her war film The Hurt Locker (2009). She has always been comfortable with directing movies in what it's usually "man's territory". Always interested in war movies, sci-fi, action films, violence and a bizarre obsession with weaponry. Point Break is the ultimate testosterone flick, an action-packed thriller set against the Southern California surf culture. Not a movie that needs to be taken too seriously, it's a fun buddies movies which can satisfy both drinking pals and gender study intellectuals.

- Beau Travail (1999) by Claire Denis

Shot in Djibouti's desert with little money and a small cast, Beau Travail is a poetic ode to masculinity. Following a more abstract approach that resembles a fragmented sequence of memories, Denis's work has this dreamlike atmosphere which is hard to put into words. The strict and regimented military training of a group of men almost becomes a surreal dance. It follows the memories of Foreign Legion officer, Galoup, played by a great Denis Lavant (Holy Motors). The arrival of a promising young recruit, Sentain, plants the seeds of jealousy in Galoup's mind.

- American Psycho (2000) by Mary Harron

Adapted from the gruesome Bret Easton Ellis's novel, American Psycho is a satire on the "yuppie" culture, the extremism of capitalism and the rotted misogyny in Wall Street in the 80's. Christian Bale gives a career-turning performance as he perfectly captures the malevolent psyche of his character, an obsessive-compulsive metrosexual and young investment banking executive, who lives a second life as a gruesome serial killer of women. A cult!

- Chevalier (2015) by Athina Rachel Tsangari

With Lanthimos, Tsangari is among the most notable directors of the new and bizarre Greek New Wave movement. Chevalier is a savage and absurd examination on machismo, male ego and men competitiveness. In the middle of the Aegean sea, on a luxurious yacht, six male acquaintances decide to start a series of competitive games between them to determine who is the "Best in General" (In other words, "who has the longest penis"). With a premise like that, it's a shame that Tsangari approach is so dry and dull.

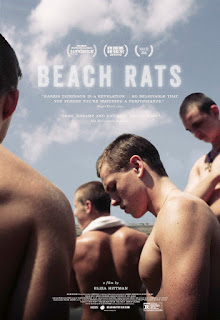

- Beach Rats (2017) by Eliza Hittman

Shot in 16mm, Beach Rats is a slow-paced analysis on sexual repression and toxic masculinity. Set against the background of Brooklyn, it centres around the bleak existence of Freddie, a young thug who spends his time with his tribe of swagger delinquent friends, while secretly talking to older men online in gay chat. Hittman intimately captures the confusion of sexual discovery and the societal pressure that often affect people living in a marginalised enviroment. However, her second film feels a bit contrived and anti-climatic

- Western (2017) by Valeska Grisebach

These lists are open to recommendations. If you have a film in mind that should be on the list please leave a comment and tell us what you think.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Labels:film, cinema, review

brutal

cannes

child abuse

female director

greenway

hitman

joaquin phoenix

man

masculinity

phantom thread

psycho

ramsay

taxi driver

tilda swinton

we need to talk about kevin

you were never really here

Comments

Post a Comment